-

Make Federalism Great Again

Americans don’t want federalism. But they should. I have convinced two friends that I am right and they offered their own implementations.

-

How I Got MoviePy To Work (Again)

tl;dr:

-

The US Isn't Rome, It's Spain

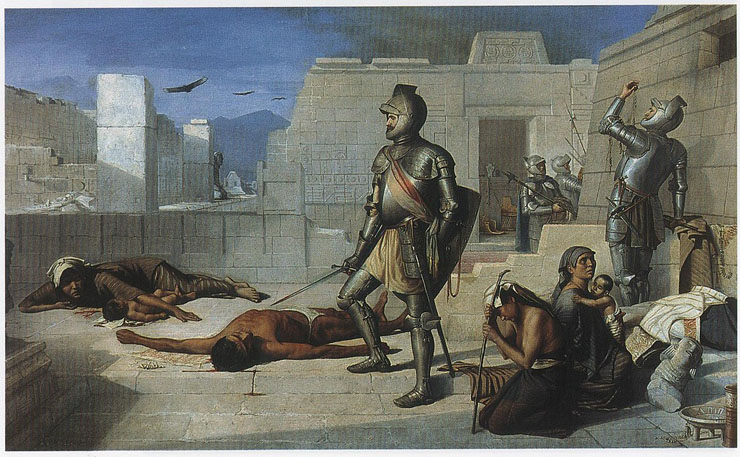

Félix Parra's Episodes of the Conquest: Massacre of Cholula, 1877, oil on canvas. -

A Point About US Conservatives

There’s this New York Review of Books article about the resurgence of the political right in Europe. Far right movements around the world are coalescing around an anti-immigrant, protectionist, social conservative message.

-

Pragmatism for Creatives

I’ve been offered a lot of good advice that I ignored. I’m well on my way to my thirties, so now I guess it’s my turn to proffer some unheeded advice of my own.

-

The Debunked Backfire Effect and Its Implications

-

Politics as Religion

“Politics at its most basic isn’t a Princeton debating society,” wrote Matt Taibbi, “[i]t’s a desperate battle over who gets what.” If that’s true, then it’s probably best if that fight remains a boring one.